Get Enough Confidence to Build Your Product

Frederik Vosberg

I’ve had a chat with a friend last week. He asked me how I evaluate whether an idea is viable or not.

“Isn’t it the innovator’s bias, that an idea will become profitable? So, how do you evaluate ideas in the beginning? I would love to found a start-up myself some time, but I have to become an industry expert first to make such a bet!”

To be honest, you don’t. At least not by planning. The most reliable way to find out is to learn along the way. Emphasis on learning!

But let’s start where you might be at now. Let me walk you through the way of developing a new product like a bet and fix this approach step by step.

Starting with the MVP

So, you start out and know that it’s risky to build a new product. Usually, there are two ways people respond to that problem. They either want to work on the plan until they feel confident, or they attempt to make the first version as small as possible.

The first approach can become quite problematic. Launching a new product is innately complex. That means that you can’t plan what will happen in advance. Most plans crumble as soon as they meet the real world. There is useful information you can gather, but the amount is limited. Overdoing this step will make your plan more detailed, but not more reliable. This leads to false confidence in the plan. In the end, the founder gets so invested in her idea, that she isn’t able to pivot anymore.

The second approach is better. Only the user’s behaviour will tell whether your product will be successful. So, it makes sense to limit the investment in the first version to the bare minimum. This means that you will have much time, money, and energy left to adapt to the user's needs.

But what if nobody cares about the launch of your first small version? You lost the investment, and you can’t learn because there is no user to learn from. Luckily, there is a way out to know what the first version should look like without building it.

Understand the customer’s problem first

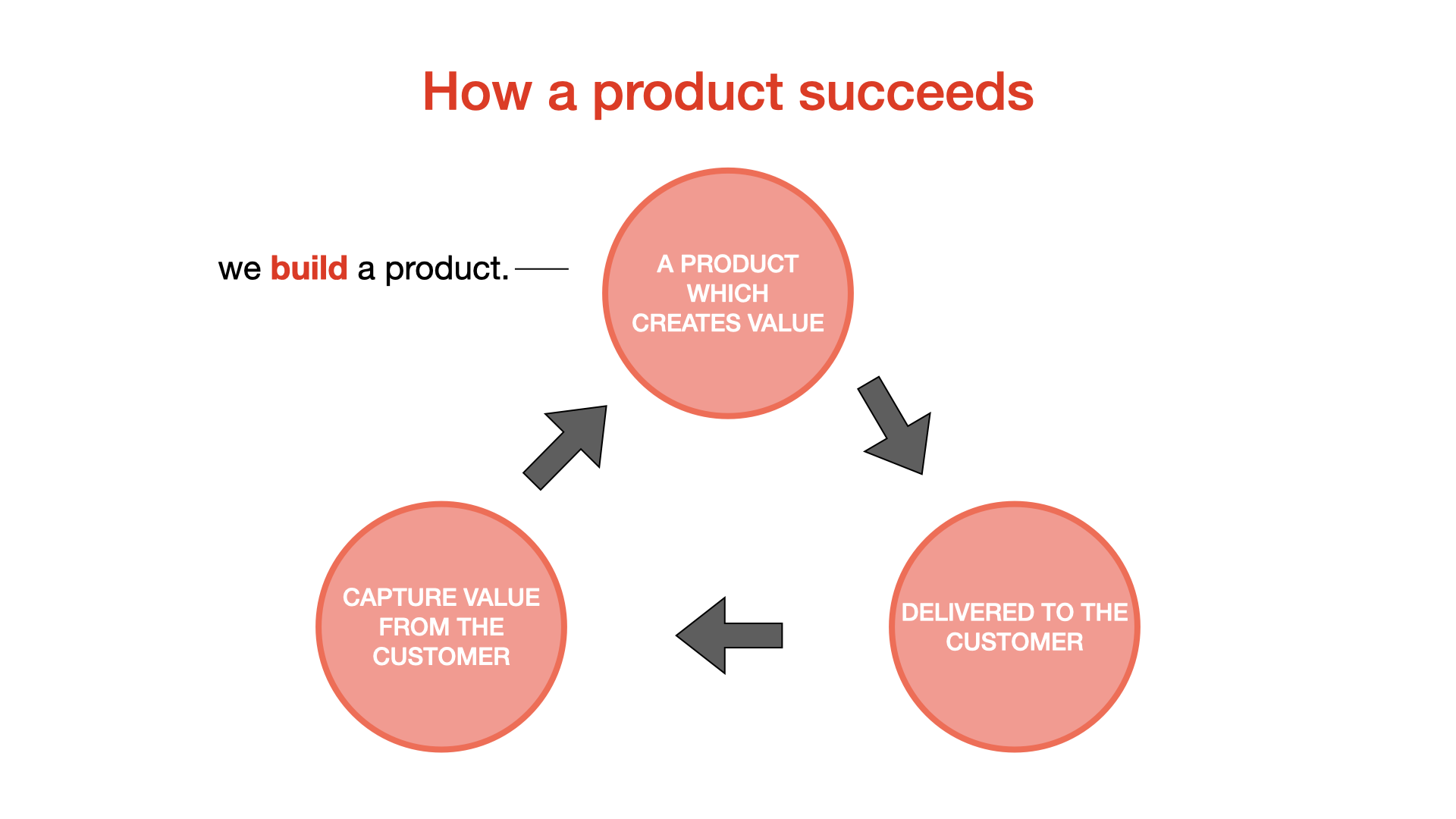

How can we identify a problem worth solving without building a small product? Well, let’s think about what a successful product does. It is successful because someone pays for it, in some way or another. This means that it creates value, and it is able to deliver this value to the customer.

To be more specific, the value perceived by the customer has to be higher than the amount we want to charge for it.

Whether there is a problem with a high perceived value, is something you can research without building the product. How do people solve this problem today? Do they invest time or money? Are they frustrated?

At first, you can just research these questions. But you’ll reach a point where you can learn faster by conducting interviews.

If you have built up enough confidence or want to speed up the process, you can do a quantitative experiment. You can market your product without building it. This is called a Fake Door MVP. You build a landing page where you promote it. Then you drive customers to this site and push them to declare their buying intention. When they do, you have to put your cards on the table and say you haven't built this product yet. This feels rude, but it’s not what you say, it’s how you say it. You can thank them and offer a heads-up when you have launched.

This approach has a pitfall, though. What if you find a problem worth solving, but the market is too small? How many customers do you need anyway to be profitable? This is why I add a traction model to my modeling process.

Model your business first to see what is truly critical

In our last approach, we’ve looked into the desirability of our product only. While examining that part, we should check if the market size might become a problem down the road. Or frankly speaking: Can we make enough money to be profitable selling it?

This equation consists of some variables. In its easiest form, it is the number of purchases multiplied by the price. But it is very hard to estimate how much you will sell. This is where business plans get very precarious. I often see assumptions of a market share you want to reach with your product. These are assumptions you can’t really examine early on.

A workaround is to start with a minimum success criteria. How much money do we have to make to succeed? This should be the bare minimum you really need.

Let’s look at an example. For simplicity, I’ll concentrate on a simple business where you sell a book. This is a one-sided business model with a one-time fee. But it works the same for more complex models as well.

We want to generate a nice little passive income of 120,000 € annual recurring revenue (ARR). So, let's set our price to 20 € per book. This means that we need to sell 6,000 copies per year to reach that revenue goal. Let’s break that down to a smaller time frame to test it faster. 6,000 copies a year means 500 per month or ~16,5 per day.

We want to sell this book on our website where we expect a conversion rate of 1%. That means, that 1% of our visitors buys one copy. This is just a guess, and we’ll adapt it while we learn down the road. With the conversion rate and the goal of purchases, we can calculate the number of visitors we need each day. 16,5 purchases x 1% conversion = 1,650 visitors each day.

- Is 20€ a price point the customer is willing to pay?

- When we want to sell this book on our website, can we meet the target of 1% conversion?

- Is it plausible that we can drive 1,650 potential customers per day to our website? (500 sold copies times 1% conversion rate = 50,000 per month)

Down the road, we might learn that one of our assumptions is wrong. Maybe it turns out, for example, that it’s just a book for a small niche. We did an estimation and 1,650 potential customers each day seems too much of a stretch. How you can do such an estimation is part of another article. In that estimation, we’ve assessed, that 825 visitors per day may seem more realistic. In that case, there are two other variables we have to adapt to meet our minimum success criteria. One possible lever is to double the price to 40 € per copy. The other is to increase the conversion rate to 2%. We have to decide what adjustments seem realistic and have to collect evidence about the new assumptions.

This is a real opportunity to learn fast and early. While this step seems complicated in the beginning, it should be a fast one. This is just the first model, and we have to learn through evidence, not thinking. As mentioned earlier, working too long on your business model can cause unjustifiable confidence.

What does the plan look like now?

To wrap this up, how does the process look now?

- Model a viable business and identify the riskiest assumptions.

- Start learning by conducting experiments.

- Adapt your business model step by step.

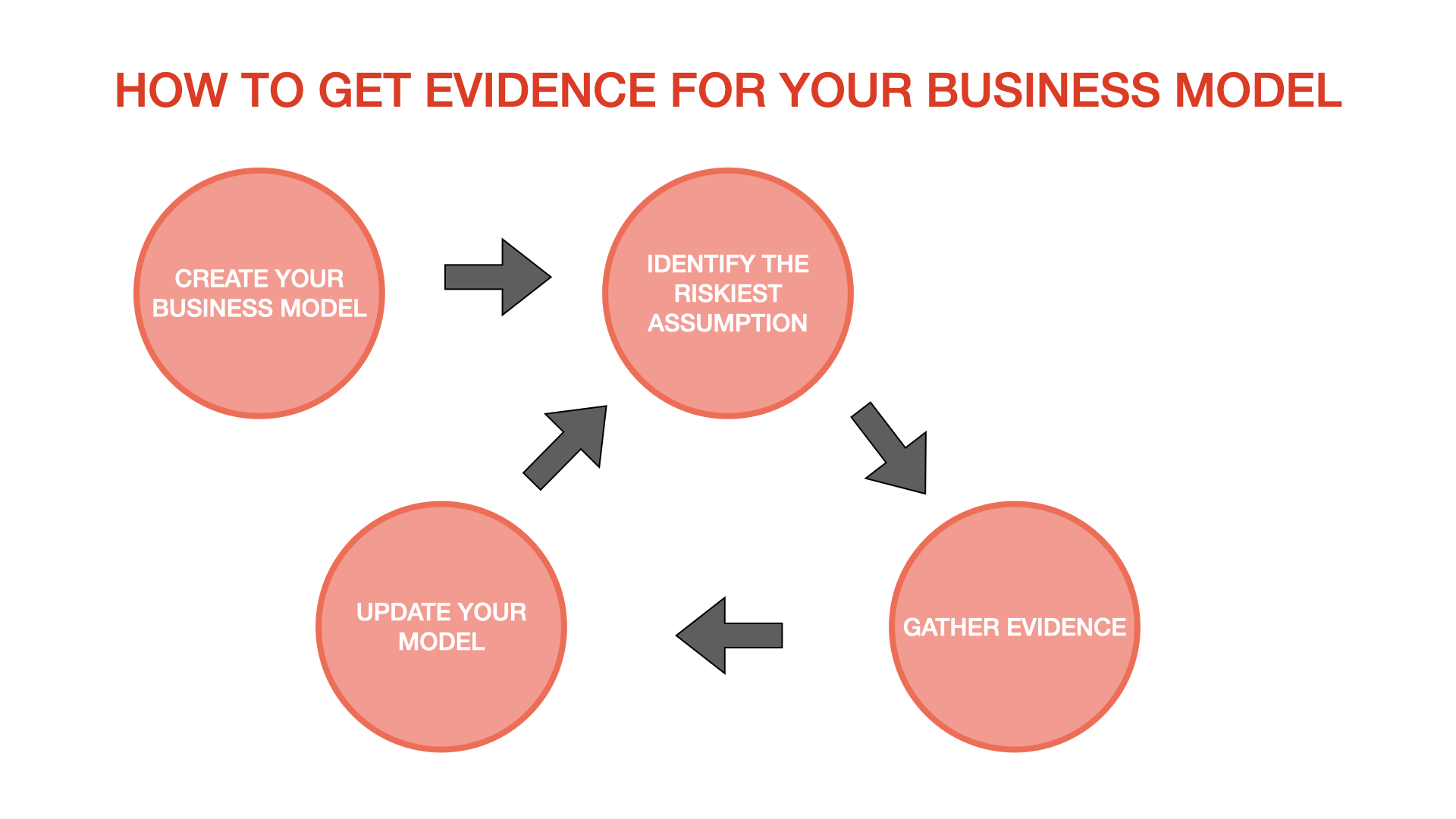

We built a model of different assumptions. They are neither true nor false. Our main job as entrepreneurs is to learn about them. And we should start with the most critical and the riskiest ones. If you find out that one is wrong, you have to adapt your model. This will lead to adjustments to other hypotheses as well.

You see that the business model is a very fluid thing, especially in the beginning. And it is a cycle that continues.

- Create/Update your model

- Identify the riskiest part

- Gather evidence about that part

- Update your model

Conclusion

When you start out, you have a vision for your product. That particular version you imagine is probably not viable. But instead of being discouraged by that, you draft a viable model consisting of different moving parts. Each part is an assumption you can test separately. And every test creates learnings about your business model. This will force you to adapt your model until you find a viable one based on real customer needs. This one won’t be based on gut feeling, but on evidence.

The approach isn’t about science, though. It is about building confidence while moving fast. With every experiment, you attempt to gather evidence as fast and cheaply as possible. At some point, you’ll have gathered enough evidence for the moment of truth. Your next experiment will be actually the first version of your product. 🚀